A chance encounter during a drunken night out was the unlikely catalyst for breakdancer Sunny Choi’s journey to the Olympic Games.

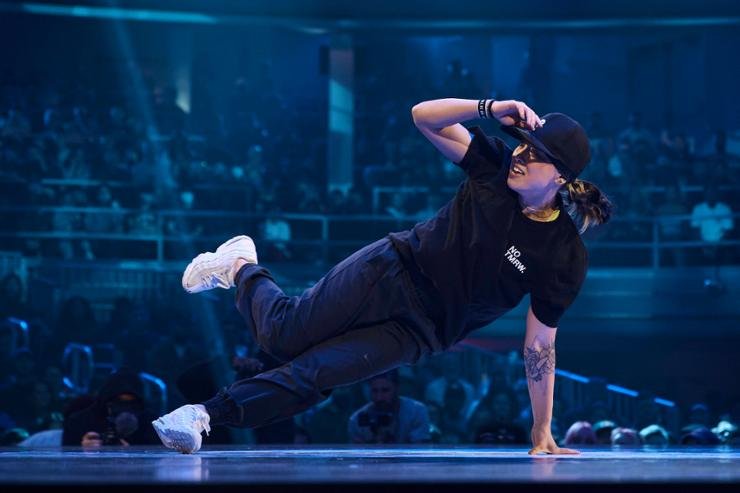

The 35-year-old American will showcase her skills before a global audience in Paris when breaking makes its debut on the Olympic stage.

Choi is the beneficiary of efforts to attract younger fans to the Olympics, a move which led to breaking’s inclusion for the first time.

But as Choi freely admits, the Olympics was the last thing on her mind when she took up the sport.

A freshman student at the University of Pennsylvania’s prestigious Wharton School of Business, Choi stumbled into breaking by accident.

“When I got to college I was pretty lost and I didn’t know what I wanted to do,” she recalled. “One night I was out late, and I was drunk. And there were some people dancing on campus and I was like ‘Oh that looks fun’.”

Choi, who had previously pursued gymnastics, subsequently attended her first breaking class and realized she had found her vocation.

“They had me try some stuff, like going upside down, and I was like ‘Oh, I love being upside down.’ This is great.

“Over time I fell in love with exploring my body’s physical limits and artistic expression. Because I’d never done anything creative in my life before.”

What began as a hobby soon became a competitive pastime.

“I’m one of those people who’s like, you either go all in or nothing,” Choi said. “Next thing I knew I’m like at a World Championships. And then they announced breaking was in the Olympics.”

‘Scary’ sacrifices

There have been sacrifices along the way.

In early 2023, Choi resigned from her lucrative job as director of global creative operations for the Estee Lauder cosmetics giant in order to pursue breaking full-time.

“It was scary because I knew that I wasn’t gonna have the financial stability that I’d always had in my life,” Choi says.

“I’ve worked my whole life to have financial stability. So to give it up for this dream that may or may not happen was really scary.”

Work colleagues were supportive.

“When you tell people you’re quitting so you can compete at the Olympics, they don’t try to and talk you out of it,” she said. “My boss was like ‘I really want you to stay but I have no business asking you to stay given what you’re leaving for.'”

Her parents, however, were more circumspect.

“At first they were like ‘Oh, yeah — but when are you going to quit and have a family and have kids?,” Choi says.

“But when I started competing internationally and they started seeing some of the media, they began to realize this is a real thing, they kind of slowly came around.”

Choi will be one of 16 “B-girls” competing for a medal in Paris, with 16 “B-boys” taking part in the men’s event. Competitive breaking sees athletes face off in “battles”, earning marks from judges for improvised routines which incorporate certain recognized moves.

Unlike sports such as figure skating or gymnastics, breakers have no say in the music they are required to perform to.

“I have no idea what I’m gonna do,” Choi says. “I just walk out there and the music turns on, and if it’s great I’m gonna go kill it, and if it’s not, well, hopefully things go well.”

Unlike other athletes in her chosen sport, Choi says she finds it difficult to adopt the gladiatorial mindset favored by rivals.

“A lot of breakers go out and are super aggressive, like want to rip your head off aggressive,” she says. “I go in with a smile. When I first started breaking a lot of people said ‘You can’t do that, you need to be aggressive.

Act like you want to punch somebody in the face.’ But there is no part of me that wants to be like that. So I just kept smiling; and now it’s become like my signature.”

Choi and breaking’s moment in the Olympic spotlight will be fleeting however. The sport will not feature at the Los Angeles 2028 Olympics, a fact Choi agrees is bittersweet.