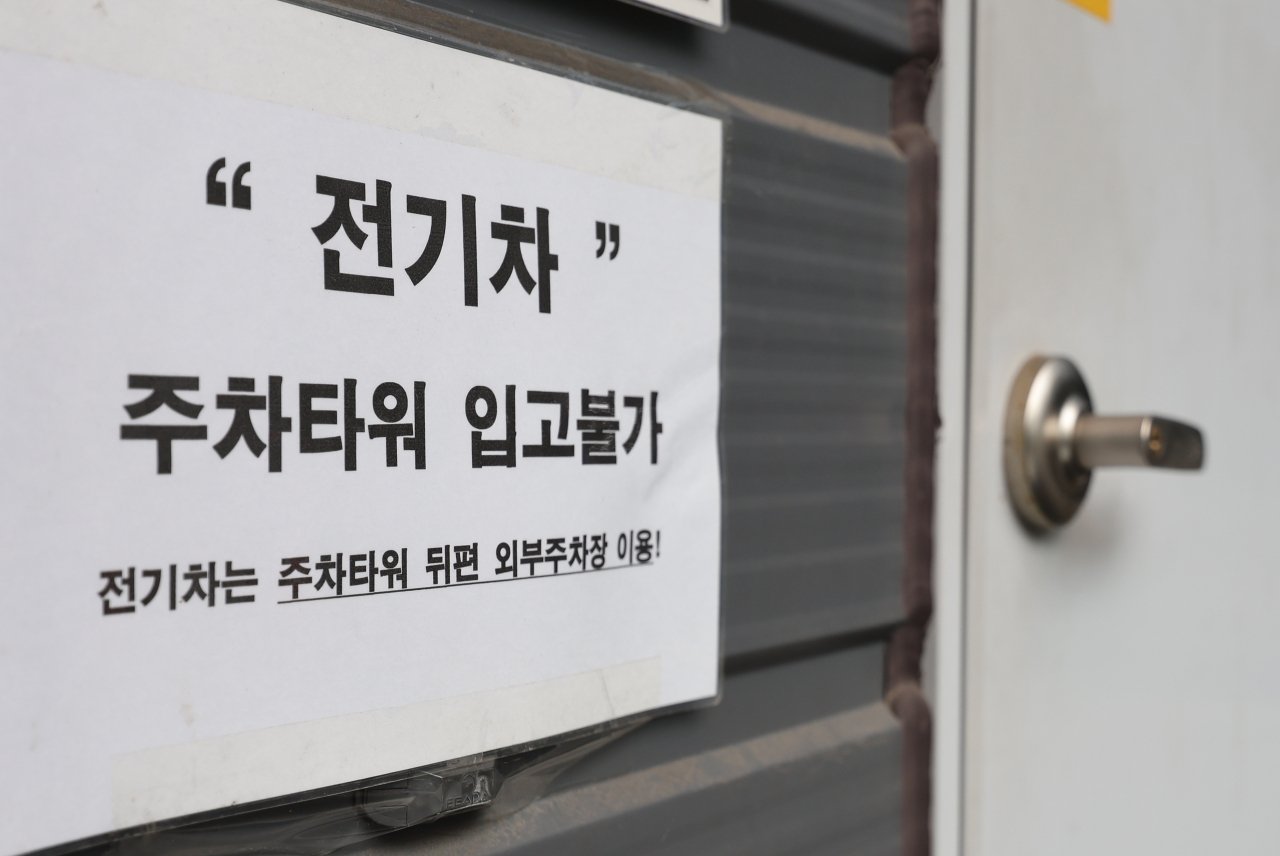

“No EVs permitted in underground parking areas.”

These signs have recently popped up at some apartment complexes and office buildings across South Korea, a response to a severe fire earlier this month. An electric vehicle ignited in the underground parking lot of an apartment building in Cheongna International City, Incheon, triggering widespread fear and leading some apartment managers to ban EVs from these spaces entirely.

The fire began with a stationary, uncharging Mercedes-Benz EQE 350 and quickly spread, burning or destroying 140 vehicles and damaging the building’s electrical and plumbing systems. This left about 480 households without electricity and water, currently forcing 800 residents into temporary shelters at a nearby school.

The exact cause of the fire remains unknown, and investigations by the police are underway.

Meanwhile, businesses are also taking action. In response to the fire, LG Display has moved the EV chargers at its Paju plant from underground parking to ground level. Similarly, the Korea International Trade Association plans to relocate all EV charging stations from the third basement floor of the World Trade Center Seoul and COEX to ground-level parking lots much sooner than the originally planned date of 2028.

While fears about EV fires are understandable, experts assure us that EVs are not more likely to catch fire than gasoline cars. The real challenge lies in managing these fires, particularly underground. They point to the inadequate safety measures in underground parking spaces, which are more common in Korean cities than in any other country, as the true risk factor. These outdated systems can make any fire, regardless of the vehicle type, far more hazardous.

Are EVs more fire-prone?

Many people believe EVs are more likely to catch fire because of their batteries. An EV safety survey by the Korea Transportation Safety Authority last year found that about half of EV owners in Korea worry most about fire risks during crashes or charging.

Statistics from the Ministry of Transportation and the National Fire Agency show that EV fires in Korea have indeed increased, from one in 2017 to 72 in 2023. This rise mirrors the growing number of EVs on the road. However, when comparing the incidence of fires, EVs are not significantly more prone to ignite than traditional internal combustion engine vehicles. In 2023, there were 1.3 EV fires per 10,000 vehicles, compared to 1.9 for ICE vehicles.

The heightened focus on EV fires seems to stem from the extent of the damage they cause. Between 2021 and 2023, property damage from EV fires totaled 3.054 billion won ($2.22 million), averaging 23.42 million won per fire. In contrast, the average damage per ICE vehicle fire is 9.52 million won.

“EVs are not inherently more fire-prone. But when an EV battery does catch fire, it might lead to a major blaze that’s harder and takes longer to put out. Also, EVs generally cost more than ICE vehicles, which contributes to the higher damage costs,” an official from the National Fire Agency explained.

Are EV fires tougher to tackle underground?

Yes, electric vehicle fires in underground spaces can be particularly challenging due to the intense heat from lithium-ion battery thermal runaway, which can reach up to 1,000 degrees Celsius. Standard powder fire extinguishers are often ineffective because they can’t cool the battery from the inside.

Instead, large equipment like mobile fire extinguishing tanks, which can immerse the entire vehicle, are required. However, getting such equipment into underground parking lots is tricky. For example, during the Incheon EV fire, firefighters struggled to bring a mobile water tank designed for EV fires into the underground lot as thick smoke hindered their efforts.

Furthermore, the absence or malfunctioning of basic safety features like sprinklers in Korea’s underground parking spaces magnifies these challenges.

A survey conducted earlier this year by the Gyeonggi Province Fire Department found that many older apartment buildings in the region lack sprinklers in their underground parking lots. Specifically, 61.6 percent of buildings over 20 years old did not have this essential safety feature.

According to a Korea Land and Housing Corporation report in May, it was found that properly functioning upper sprinklers can effectively prevent fire spread between EVs, and adding lower sprinklers can reduce the risk of an EV battery fire by half.

Should EVs be banned underground?

“While some cities in Germany and Belgium have imposed such bans after isolated accidents, South Korea’s widespread use of underground parking requires a different approach,” said Dr. Choi Myoung-young from the Korea Fire Protection Association.

Experts in disaster prevention suggest that rather than banning EVs, efforts should focus on ensuring that existing safety facilities are functional. The Incheon Fire Service confirmed on Monday that sprinklers, the most basic safety device, were not activated during the Cheongna EV fire, which worsened the damage.

There are clear examples demonstrating the effectiveness of functional safety systems. For instance, when a Chevrolet Bolt EV caught fire in an underground parking lot in Gunsan, North Jeolla Province, on May 8, the activated sprinklers extinguished the fire within 45 minutes, preventing any casualties.

“In the Cheongna accident, I think one of the biggest points of failure was that the sprinklers didn’t kick in, leading to greater destruction and taking 8 hours to be extinguished,” said Professor Lee Ju-young, who specializes in fire and disaster prevention at Kyungpook National University.

“Sure, EVs can have longer burn times than gasoline cars, but with properly maintained sprinklers and other basic safety measures, we can stop a fire in its tracks. It’s essential to first regularly check and maintain these safety systems in underground parking spaces rather than implementing an extreme measure like completely banning EVs,” he added.